OSLS Linus Torvalds believes the technology industry’s celebration of innovation is smug, self-congratulatory, and self-serving.

The term of art he used was more blunt: “The innovation the industry talks about so much is bullshit,” he said. “Anybody can innovate. Don’t do this big ‘think different’… screw that. It’s meaningless. Ninety-nine per cent of it is get the work done.”

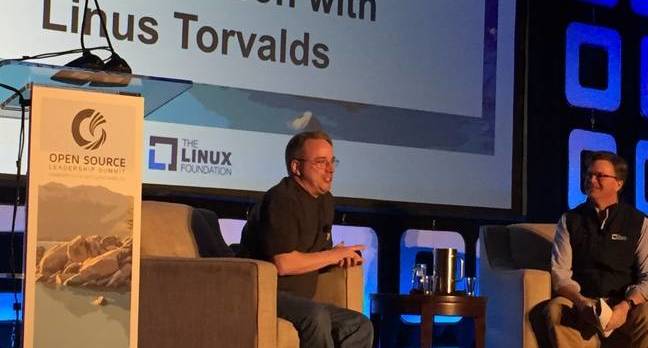

In a deferential interview at the Open Source Leadership Summit in California on Wednesday, conducted by Jim Zemlin, executive director of the Linux Foundation, Torvalds discussed how he has managed the development of the Linux kernel and his attitude toward work.

“All that hype is not where the real work is,” said Torvalds. “The real work is in the details.”

Torvalds said he subscribes to the view that successful projects are 99 per cent perspiration, and one per cent innovation.

As the creator and benevolent dictator of the open-source Linux kernel, not to mention the inventor of the Git distributed version control system, Torvalds has demonstrated that his approach produces results. It’s difficult to overstate the impact that Linux has had on the technology industry. Linux is the dominant operating system for servers. Almost all high-performance computing runs on Linux. And the majority of mobile devices and embedded devices rely on Linux under the hood.

The Linux kernel is perhaps the most successful collaborative technology project of the PC era. Kernel contributors, totaling more than 13,500 since 2005, are adding about 10,000 lines of code, removing 8,000, and modifying between 1,500 and 1,800 daily, according to Zemlin. And this has been going on – though not at the current pace – for more than two and a half decades.

“We’ve been doing this for 25 years and one of the constant issues we’ve had is people stepping on each other’s toes,” said Torvalds. “So for all of that history what we’ve done is organize the code, organize the flow of code, [and] organize our maintainership so the pain point – which is people disagreeing about a piece of code – basically goes away.”

The project is structured so people can work independently, Torvalds explained. “We’ve been able to really modularize the code and development model so we can do a lot in parallel,” he said.

Technology plays an obvious role but process is at least as important, according to Torvalds.

“It’s a social project,” said Torvalds. “It’s about technology and the technology is what makes people able to agree on issues, because … there’s usually a fairly clear right and wrong.”

But now that Torvalds isn’t personally reviewing every change as he did 20 years ago, he relies on a social network of contributors. “It’s the social network and the trust,” he said. “…and we have a very strong network. That’s why we can have a thousand people involved in every release.”

The emphasis on trust explains the difficulty of becoming involved in kernel development, because people can’t sign on, submit code, and disappear. “You shoot off a lot of small patches until the point where the maintainers trust you, and at that point you become more than just a guy who sends patches, you become part of the network of trust,” said Torvalds.

Ten years ago, Torvalds said he told other kernel contributors that he wanted to have an eight-week release schedule, instead of a release cycle that could drag on for years. The kernel developers managed to reduce their release cycle to around two and half months. And since then, development has continued without much fuss.

“It’s almost boring how well our process works,” Torvalds said. “All the really stressful times for me have been about process. They haven’t been about code. When code doesn’t work, that can actually be exciting … Process problems are a pain in the ass. You never, ever want to have process problems … That’s when people start getting really angry at each other.”